You have been in the field talking to users and you now find yourself with a massive amount of audio, notes, video, pictures, and interesting impressions. All that information can be overwhelming, and it’s difficult to know where to start to make sense of all the data. Here, we will teach you how to go from information chaos to patterns and themes that represent the most interesting aspects of your data and which you can use as the foundation for personas, user scenarios and design decisions. When you have carried out user interviews, the next step is to analyze what people have told you. Depending on the complexity of your project, this can be a simple or a complex task, but no matter what your project is, it’s important that you follow certain guidelines for how to analyze your interviews. Although you might feel like you have a pretty good idea of what people have told you and you are eager to get started implementing your insights, doing a proper analysis is important for the validity of your results. There is a lot going on in an interview situation, and it’s easy to overlook information that doesn’t fit with your preconceived assumptions of what people were going to say and do during your interviews. A proper analysis will ensure that you go through your data in a systematic and thorough manner. A proper analysis also makes it easy for other people to understand exactly how you reached your various conclusions about your participants and will make your results much more trustworthy. Analyzing your results takes time, especially if your purpose is broad and explorative. But if your time is limited, it’s always better to narrow the scope of your study than to skip steps in the analysis phase and jump straight to acting on your results. © Highway Agency, CC BY 2.0 It’s important that you properly analyze your interviews, but there is no single right way to perform qualitative data analysis, and the method you choose primarily depends on the actual purpose of your study. Here, we will focus on one of the most common methods for analyzing semi-structured interviews: thematic analysis. A thematic analysis strives to identify patterns of themes in the interview data. One of the advantages of thematic analysis is that it’s a flexible method which you can use both for explorative studies, where you don’t have a clear idea of what patterns you are searching for, as well as for more deductive studies, where you know exactly what you are interested in. An example of an explorative study could be conducting interviews at a technical workplace in order to obtain an understanding of the technicians’ everyday work lives, what motivates them, etc. A more deductive study could be conducting interviews at a technical workplace in order to find out how technicians use a specific technology in order to handle safety-critical situations. No matter which type of study you are doing and for what purpose, the most important thing in your analysis is that you respect the data and try to represent your interview as honestly as possible. When you share your results with others, you should be transparent about everything in your research process, from how you recruited participants to how you performed the analysis. This will make it easier for people to trust in the validity of your results. People who don’t agree with your conclusion might be critical of your research results, but if you know that you have done everything possible to represent your participants and your research process honestly, you should have no problem defending your results.

“Analysis involves a constant moving back and forward between the entire data set, the coded extracts of data that you are analysing, and the analysis of the data that you are producing.”

—Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, Authors and qualitative researchers in psychology

In this video, professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London and expert in qualitative user studies Ann Blandford provides an overview of what an analysis process can look like.

Thematic analysis is used in many different research fields, but the steps are always the same, and here we build our detailed description of the steps on a famous article, by qualitative researchers in psychology Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, called “Using thematic analysis in psychology”. We describe the process as you might do it in a business setting; so, if you are conducting interviews for academic purposes, you should look up the original article.

During the first phase, you start to familiarize yourself with your data. If you have audio recordings, it’s often necessary to perform some form of transcription, which will allow you to work with your data. In this phase, you go through all your data from your entire interview and start taking notes, and this is when you start marking preliminary ideas for codes that can describe your content. This phase is all about getting to know your data.

How much you need to transcribe will vary depending on your project. If you are performing a broad and exploratory analysis, you may need to transcribe everything that was said and done during the interview, as you don’t know in advance what you are looking for. If you are searching for specific topics, you will probably only need to transcribe those parts of the interview that pertain to that topic. In some cases—e.g., when the interview is a minor part of a larger user test or observation project—writing a detailed summary or summarizing specific themes can be sufficient. When you consider how much to transcribe, take Braun and Clarke’s advice: “What is important is that the transcript retains the information you need, from the verbal account, and in a way which is ‘true’ to its original nature”.

Whether you transcribe it yourself or pay someone to do it for you will depend on your budget and your time. Some researchers prefer to do it themselves because they can start making sense of the data as they transcribe; others feel as though they can use their time more efficiently by reading the finished transcripts that someone else has made.

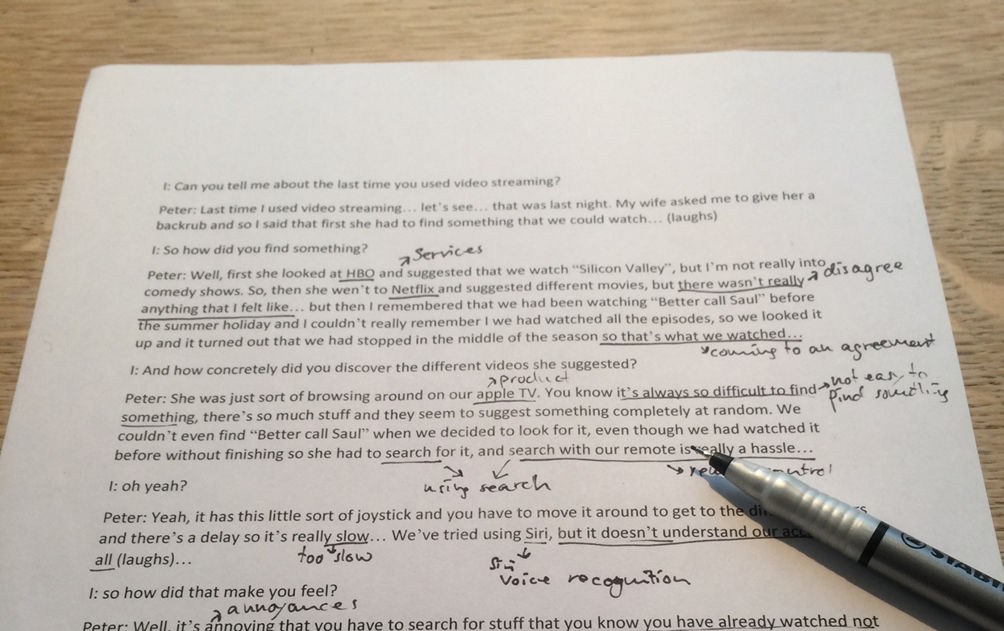

In phase 2, you assign codes to your data. A code is a brief description of what is being said in the interview; so, each time you note something interesting in your data, you write down a code. A code is a description, not an interpretation. It’s a way to start organizing your data into meaningful groups. As an example, let’s try to code a snippet from an interview about video streaming:

“I: So how did you find something?

Peter: Well, first she [his wife] looked at HBO and suggested that we watch ‘Silicon Valley’, but I’m not really into comedy shows. So, then she went to Netflix and suggested different movies, but there wasn’t really anything that I felt like… but then I remembered that we had been watching ‘Better call Saul’ before the summer holiday, and I couldn’t really remember if we had watched all the episodes, so we looked it up and it turned out that we had stopped in the middle of the season; so, that’s what we watched…”

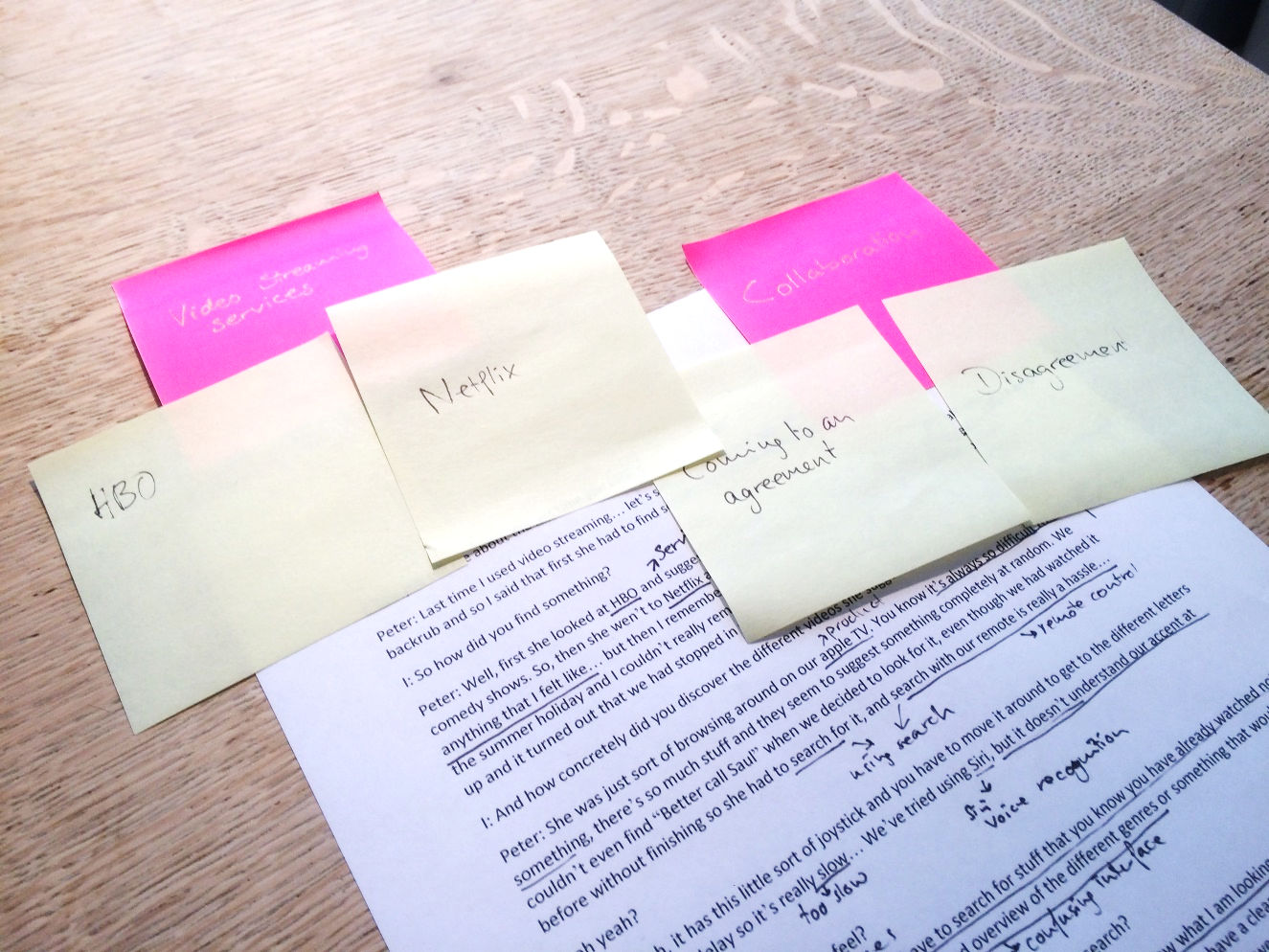

You can give this section multiple codes (and it’s perfectly fine to give one section multiple codes) depending on your interests. If you are interested in different streaming services, you could use the codes “Netflix” and “HBO”. If your interests are broader or if you are—e.g.—interested in how people collaborate, you could use the code “coming to an agreement”. So, which codes you use depend on what is being said and on the purpose of your research. Your coding also depends on whether you are performing an exploratory analysis, where the themes depend on the data, or a deductive analysis, where you search for specific themes.

© Ditte Hvas Mortensen and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

There is no clear cut-off between phase 1 and phase 2, and initial coding often takes place during the familiarization phase. There is specific software for coding, but you can also code by taking notes on a printed transcript or by using a table in a Word document. The most important thing is that you can match the code to the section of the interview that it refers to. Once you have coded all your data, the next step is to collate all the sections that fit into each code—e.g., collate all sections in your interviews with the code “Netflix”. If you are using pen and paper, you will have to copy sections that have multiple codes so that you can place them in more than one code category. If you are coding digitally, you can just use copy-paste. Braun and Clarke recommend that you code for as many potentially interesting themes as possible and that you keep a little of the data surrounding your coded text when you do the coding; that way, you won’t lose too much of the context.

© Ditte Hvas Mortensen and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

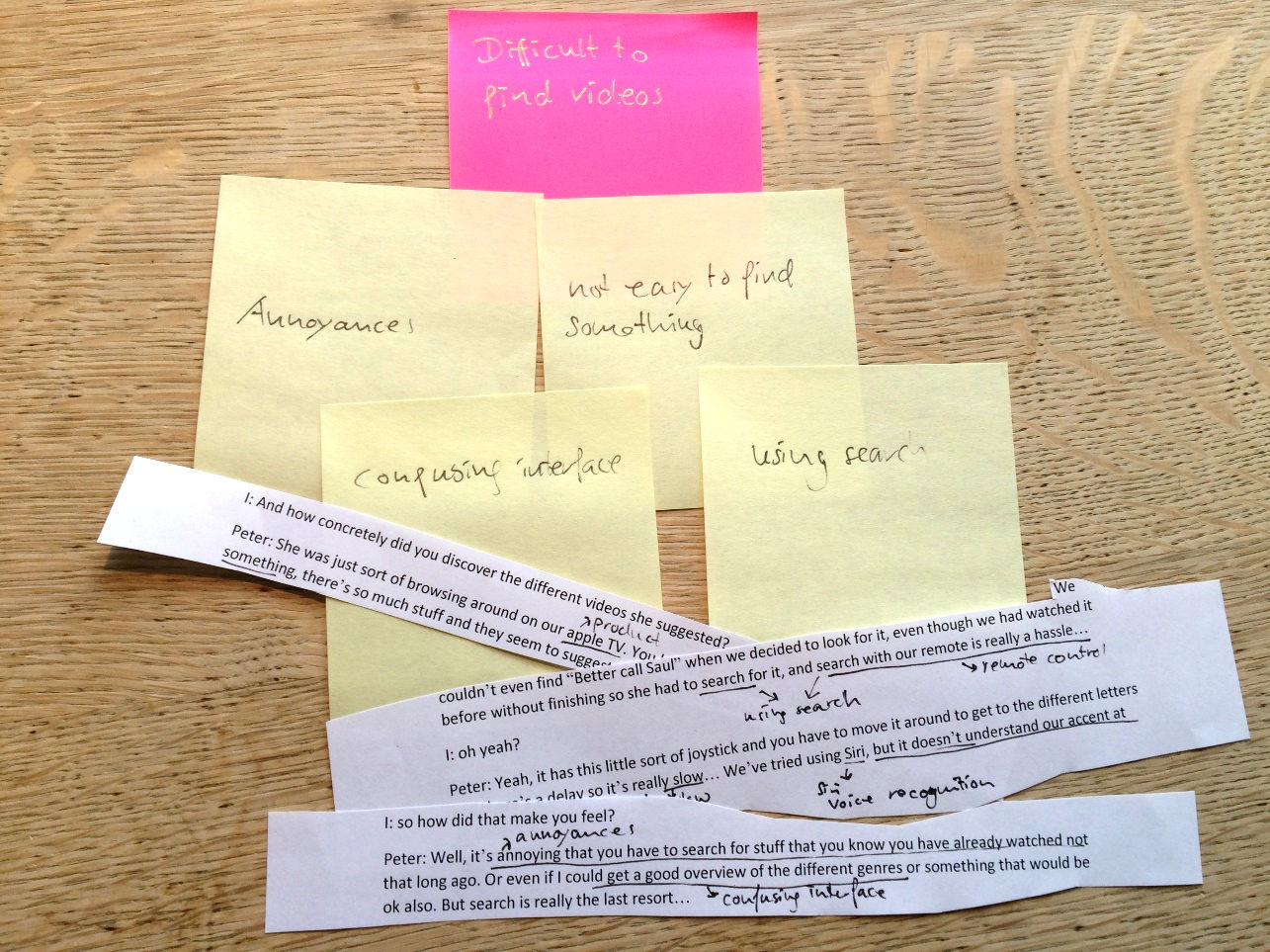

Whereas codes identify interesting information in your data, themes are broader and involve active interpretation of the codes and the data. You start by looking at your list of codes and their associated extracts and then try to collate the codes into broader themes that say something interesting about your data. As an example, you could combine the codes “Netflix” and “HBO” into a single theme called “Streaming services”. Searching for themes is an iterative process where you move codes back and forth to try forming different themes. Drawing a map of your codes and themes or having codes on sticky notes that you can move around can help you visualize the relationship between different codes and themes as well as the level of the themes. Some themes might be subthemes to others. In this process, not all codes will fit together with other codes. Some codes can become themes themselves if they are interesting, while other codes might seem redundant, and you can place them in a temporary mixed theme. At this point, you shouldn’t throw away codes that don’t seem to fit anywhere, as they may be of interest later.

During phase 4, you review and refine the themes that you identified during phase 3. You read through all the extracts related to the codes in order to explore if they support the theme, if there are contradictions and to see if themes overlap. In the words of Braun and Clarke, “Data within themes should cohere together meaningfully, while there should be clear and identifiable distinctions between themes.” If there are many contradictions within a theme or it becomes too broad, you should consider splitting the theme into separate themes or moving some of the codes/extracts into an existing theme where they fit better.

© Ditte Hvas Mortensen and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

You keep doing this until you feel that you have a set of themes that are coherent and distinctive; then you go through the same process again in relation to your entire data set. You read through all your data again and consider if your themes adequately represent the interesting themes in your interview and if there is uncoded data that should be coded because it fits into your theme. In this process, you might also discover new themes that you have missed. Phase 4 is an iterative process, where you go back and forth between themes, codes, and extracts until you feel that you have coded all the relevant data and you have the right number of coherent themes to represent your data accurately. In this iterative process, you might feel as though you can keep perfecting your themes endlessly, so stop when you can no longer add anything of significance to the analysis.

During phase 5, you name and describe each of the themes you identified in the previous steps. Theme names should be descriptive and (if possible) engaging. In your description of the theme, you don’t just describe what the theme is about, but you also describe what is interesting about the theme and why it’s interesting. In Braun and Clarke’s words, you “define the essence that each theme is about”. As you describe the theme, you identify which story the theme tells and how this story relates to other themes as well as to your overall research question. At this point in the analysis, you should find yourself able to tell a coherent story about the theme, perhaps with some subthemes. It should be possible for you to define what your theme is clearly. Moreover, if you find that the theme is too diverse or complex for you to tell a coherent story, you might need to go back to phase 4 and rework your themes.

What the final report looks like depends on your project; you might want your final delivery to be personas or user scenarios, but there are some commonalities you should always include. When you write up your results, there should always be enough information about your project and process for the reader to evaluate the quality of your research. Given that, you should write up a clear account of what you have done—both when you carried out the research and for your analysis. You already have a description of your themes, and you can use this as a basis for your final report. When you present your themes, use quotes from what the participants said to demonstrate your findings. Video, audio and photo examples are even more convincing, but NEVER use this without the participant’s consent. Remember; you have been talking to these participants. To you, the participants are real humans, each of whom has a set of views and a host of rights you must respect. It is your job to make the participants feel real to the people you report your findings to.

For UX projects, splitting your report up into two parts might be a good idea. Part one contains a summary of your findings in an engaging way—this could be in a presentation, via personas or user scenarios. Part two contains the background information about how you did your research and your full analysis. That way, people who are only interested in your conclusions can stick to those while people who have questions about your research can go to the detailed account of what your work entails. This will ensure the validity of your research and give you a good reference for the future when you have forgotten all the nitty-gritty details of your research project.

You can download our overview of the six steps in thematic analysis here:

Get your free template for “Steps in a Thematic Analysis”Thematic analysis describes a somewhat straightforward process that allows you to get started analyzing interview data; however, obviously, there is a lot of learning-by-doing involved in carrying out the analysis, so it pays to be aware of common pitfalls when doing a thematic analysis. Often an important thing to ensure is that your analysis delivers insights into the areas that you have promised your stakeholders to deliver insights into. If you find interesting information that is off-topic, consider diving into these topics in a follow-up project.

Show Hide video transcriptHere, Ann Blandford describes some of the pitfalls she often encounters when her students are learning to analyze interview data.

When it’s time to analyze your interview data, using a structured analysis method will help you make sense of your data. A thematic analysis is something you can use both for deductive and more exploratory interviews.

To analyze your data, follow the steps to analyze your research results to identify themes in your data:

Here, we have introduced you to all the steps at once… and that might be a bit overwhelming. But don’t worry! Just take one step at a time. The analysis process will become clearer as you progress, thereby affording you a wider scope for making what comes out of your interviews count all the more effectively.

Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke, Using thematic analysis in psychology, in Qualitative Research in Psychology, Volume 3(2), 2006

Ann Blandford, Dominic Furniss and Stephann Makri, Qualitative HCI Research: Going Behind the Scenes, Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2016

Hero Image: © Nearsoft Inc, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0